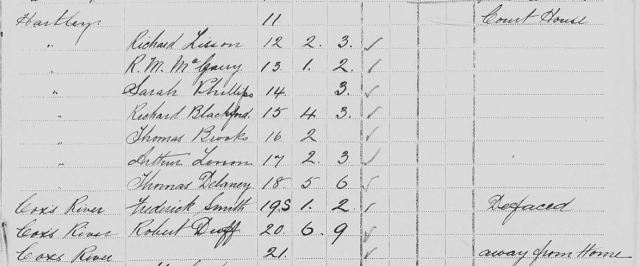

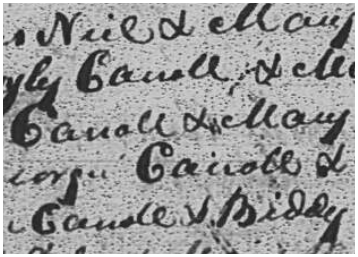

In the last post in this series, Celestina Sommer arrived at Millbank Prison on 6 September, 1856, to begin her sentence for murdering her daughter, Celestina Christmas. Her hair was cut off, she was given prison clothes and put in the probation ward. What was life like for her there?

![Handwritten record of Celestina Sommer being sent to Millbank]()

Record of Celestina Sommer being sent to Millbank *

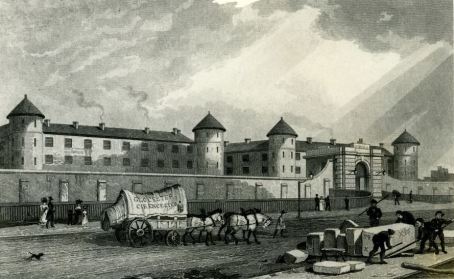

A good picture of Millbank from that era comes from Henry Mayhew and John Binny’s (M&B) 1862 book, The Criminal Prisons of London and Scenes of London Life, which I’m going to quote from several times in this post. There’s a list of further reading about women’s life in prison at the bottom.

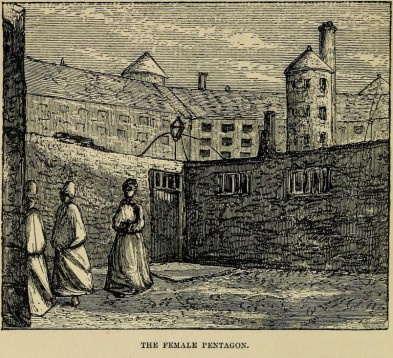

Here they describe entering the women’s pentagon, the third of the six that made up Millbank Prison’s panopticon design:

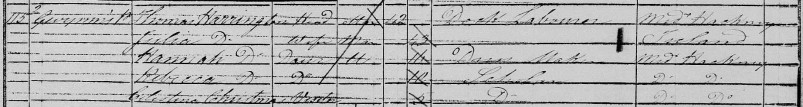

![Plan of the women's pentagon at Millbank Prison]()

The women’s pentagon at Millbank *

‘The matron now opened a heavy door that moaned on its hinges. “This is A ward, and has thirty cells in it, exactly the same as those in the male pentagon.”

‘The cells had register numbers outside, but the grated gate was considerably lighter, though equally as strong as those in the other pentagons.

‘As we peeped into one of the little cells, we saw a good-looking girl with a skein of thread round her neck, seated and busy making a shirt. The mattress and blankets were rolled up into a square bundle, as in the male cells. There was a small wooden stool and little square table with a gas jet just over it; the bright tins, wooden platter, and salt-box, a few books, and a slate, and signal-stick shaped like a harlequin’s wand, were all neatly arranged upon the table and shelf in the corner.’ M&B

They go into greater detail describing a typical cell on the men’s wards:

‘The colour of the walls we found of a light neutral tint. Beneath the solitary window, which, like all the cell windows, looked towards the “warder’s tower,” in the centre of the pentagon, was a little square table of plain wood, on which stood a small pyramid of books, consisting of a Bible, a Prayer-book, a hymn-book, an arithmetic-book, a work entitled “Home and Common Things,” and other similar publications of the Society for the Promotion of Christian Knowledge, together with a slate and pencil, a wooden platter, two tin pints for cocoa and gruel, a salt-cellar, a wooden spoon, and the signal-stick before alluded to.

‘Underneath the table was a broom for sweeping out the cell, resembling a sweep’s brush, two combs, a hair-brush, a piece of soap, and a utensil like a pudding-basin.

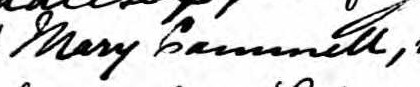

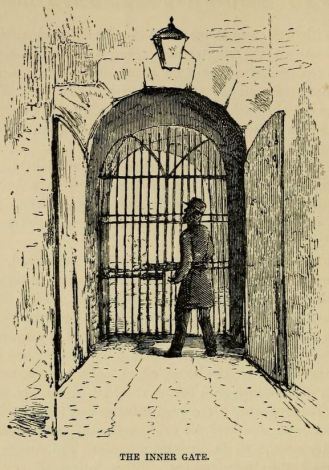

![A notice to female convicts, pinned to the wall at Millbank Prison]()

A notice to female convicts, Millbank *

‘Affixed to the wall was a card with texts, known in the prison as the “Scripture Card,” and a “Notice to Convicts” also; whilst on one side of the table stood a washing-tub and wooden stool, and on the other the hammock and bedding, neatly folded up. The mattress, blankets, and sheets, we were told, have to be arranged in five folds, the coloured night-cap being placed on the centre of the middle fold; and considerable attention is required to be paid to the precise folding of the bed-clothes, so as to form five layers of equal dimensions. The day-cap is placed on the top of the neat square parcel of bedding, which looks scarcely larger than a soldier’s knapsack.’ M&B

A day in the life of a woman prisoner at Millbank

What was a typical day like for Celestina at Millbank? I’ve turned to another fascinating contemporary book, Female life in prison, by a prison matron (FL), which was actually written by a man, Frederick William Robinson, and published in 1863.

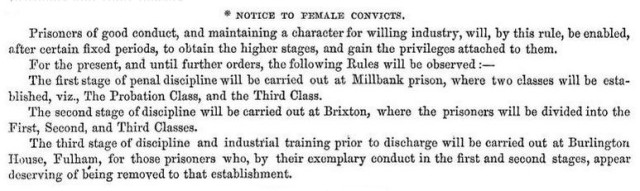

The day begins at quarter to six, he wrote, when the night guard rings a bell. ‘At six o’clock every prisoner is expected to be dressed and standing in her cell, ready to show herself to the matrons on duty’, who ‘unbolt each inner door, and fling it back to make sure the prisoner is safe and in health.’ The outer door is ‘formed of an iron grating’, which can be left locked to keep the prisoner secure but visible.

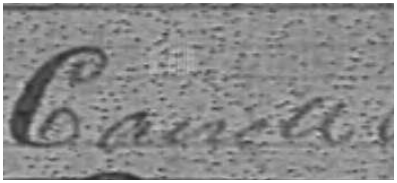

![Engraving of a guard at the inner gate, Millbank Prison]()

Guard at the inner gate, Millbank Prison *

‘The rattle, rattle of the bolts down the ward has a peculiar effect, and is the first sign of daily life.’ Some women were ‘let out to clean the flagstones in the wards, with a matron as guard over them; a few of the best-behaved dust the matrons’ rooms, and make their beds. The cells by this time are all cleaned and tidied, the bed is carefully folded up, the blankets, rug, shawl, and woman’s bonnet placed thereon, the deal table polished, and the stones of the cell scrubbed.’

At half past seven the prisoner gets a pint of cocoa ladled into her tin mug, and a four-pound loaf. After breakfast, she scrubs her ‘tin pint’, which she keeps in her cell. Work begins – ‘each woman in her separate cell, working silently, passively, and allowed no converse with her fellow-prisoners’.

At 9.15 chapel bell rings, and morning service is held half an hour later. ‘Each matron in charge of a ward is responsible for the number of women attending chapel, and the safe return to their cells.’ Presumably they go back to work, then at 12.30 ‘water is served to’ them and at 12.45 ‘the dinner-bell is rung, and each prisoner provided with four ounces of boiled meat, half a pound of potatoes, and a six-ounce loaf’ in a can, which is taken back after dinner. Then back to silent work, ‘coir-picking, shirt-making, &c’ with ‘only the voices of the matrons breaking the stillness.’

One hour a day is ‘allowed for exercise in the airing yards’, still under the rule of silence. ‘A ward of women is exercised at a time, walking ‘in Indian file’, with a prison matron in attendance, keeping a watch on her flock of black sheep.’ It’s ‘tedious and monotonous’ for the matron, ‘shivering in her in bearskin cloak’ in winter and ‘struggling against the heat’ in summer. I don’t imagine it was a barrel of laughs for the inmates, either, but at least they were able to get some exercise and fresh air.

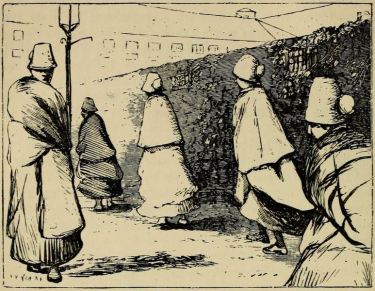

![Women convicts at exercise in Millbank Prison, wearing winter cloaks and tall hatstime]()

Millbank convicts at exercise time *

‘For one hour these convicted women tramp unceasingly round the gravelled yard, muttering to each other when at the farthest distance from the matron… plodding on in this mill-horse round for sixty minutes, with the matron at times nodding at her post.’

Work goes on till 5.30pm, ‘when gruel is served in the “pints” of prisoners’. Then ‘a few prayers are said by a matron standing in the centre of each ward, so that her voice can be heard by the prisoners standing at their doors of open iron-work. After prayers each woman answers to a name from the list called out’ and then it’s back to work ’till a quarter to eight, when the scissors are collected; reading, &c, is then allowed, till about half-past eight.’ As well as reading, the prisoners have to make their beds in this short spell of free time.

The matron turns out the gas in the cells at quarter to nine, and after that ‘it is supposed… that the prisoners are in their beds.’

At 9pm matron on night duty starts her rounds, ‘passing once an hour each cell’, looking for ‘sickness or breach of discipline… checking at times artful signals on the wall between one prisoner and another’ until the bell rings again at 5.45 am and the whole routine begins again. FL

No wonder women prisoners thought was an ‘every-day, toilsome, wearisome life’, though better than the workhouse (!)

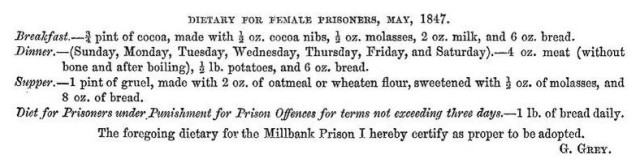

![Millbank Prison: what female prisoners ate]()

Millbank ‘dietary’. Monotonous and unhealthy

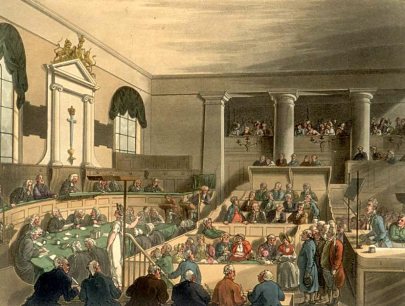

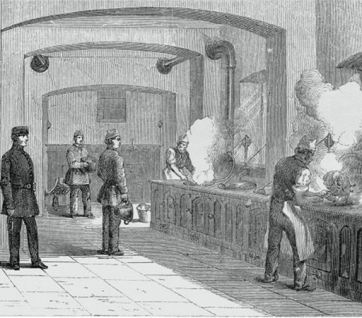

Mayhew and Binny were allowed into the kitchens at breakfast time to see the women’s breakfasts served. There were three kitchens, each one serving two of Millbank Prison’s six pentagons, and all staffed by men:

‘”This is the female compartment. Here, you see,” said the officer, pointing to the farther side of a wooden partition that stood at the end of the kitchen, “is the place where the women enter from pentagon 3, whilst this side is for the men coming from pentagon 4.” Presently the door was opened and files of male prisoners were seen, with warders, without.

‘”Now, they’re coming down to have breakfast served,” said the cook. “F ward!” cries an officer, and immediately two prisoners enter and run away with a tin can each, while another holds a conical basket and counts bread into it – saying, 6, 12, 18, and so on.

![Engraving of Holloway Prison kitchen]()

Prison kitchen (Holloway)

‘When the males had been all served, and the kitchen was quiet again, the cook said to us, “Now you’ll see the females, sir. Are all the cooks out ?” he cried in a loud voice; and when he was assured that the prisoners serving in the kitchen had retired, the principal matron came in at the door on the other side of the partition. Presently she cried out, “Now, Miss Gardiner, if you please!” Whereupon the matron so named entered, costumed in a grey straw-bonnet and fawn-coloured merino dress, with a jacket of the same material over it, and attended by some two or three female prisoners habited in their loose, dark-brown gowns, check aprons, and close white cap.

‘The matron then proceeded to serve and count the bread into a basket, and afterwards handed the basket to one of the females near her. “I wish you people would move quick out of the way there,” says the principal female officer to some of the women who betray a disposition to stare. While this is going on, another convict enters and goes off with the tin can full of cocoa.

‘Then comes another matron with other prisoners, and so on, till all are served, when the cook says, “Good morning, Miss Crosswell,” and away the principal matron trips, leaving the kitchen all quiet again – so quiet, indeed, that we hear the sand crunching under the feet [on the kitchen floor].’ M&B

This account does give a first impression that the women prisoners came to the kitchen for their breakfast, which isn’t what the ‘prison matron’ said. Perhaps what happened was that the matrons were helped by a few trusted prisoners, the sort that had the dubious privilege of cleaning the matrons’ rooms.

Millbank Prison laundry

Washing was, of course, women’s work, and very hard work it was. So in addition to coir-picking and sewing, Celestina’s fellow prisoners worked in the prison laundry, too. Mayhew and Binny paid another of their visits there:

‘We now entered the laundry, which reminded us somewhat of a fish-market, with its wet-looking, black, shiny asphalte floor. The place was empty – work being finished on the Friday. On Saturday mornings, the convicts who are usually employed to do the washing, go to school, and in the afternoon they clean the laundry, so as to have it ready for work on Monday morning. Long dressers stretch round the building; there is a heavy mangle at one side, and cloths’-horses, done up in quires, rest against the wall.

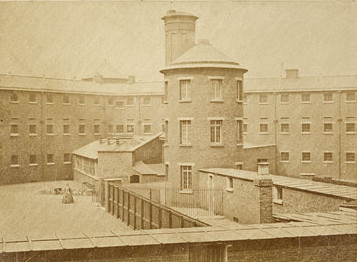

![Old photo of Millbank Prison in the 1880s showing an exercise yard and a tower]()

Millbank Prison in the 1880s

‘We are next led through the drying and getting-up room, and so into the wash-house. Here we find rows of troughs, with brass taps, for hot and cold water, jutting over them. There is a large bricken boiler at one end of the apartment, pails and tubs stand about, and a few limp-wet clothes are still on the lines. “There are only ten women washing every week now,” observed the matron; “we have had thirty-six or forty-quite as many as that. We used to do for the whole service, but at present we wash only for the female prisoners and their officers.”‘

The matron then led them back into the wards. “Generally speaking… those who have been very bad outside are found the best in prison both for work and behaviour; and the longest-sentenced females are usually the best behaved.”

“The long sentences are, mostly, for murder – child-murder,” she added; “and this is usually the first and only offence; but the others are continually in and out, and become at last regular jail people.” M&B

And, of course, it was ‘child-murder’ that Celestina Sommer was in prison for. There’s a strong implication in these accounts that women convicts were seen as either being incorrigibly criminal – poor, bad, ignorant but cunning – or one-off murderers. Though if you were locked up for a long time your chances of killing your child or abusive husband were lowered significantly…

Celestina was self-contained while she was at Millbank, not misbehaving in a way that would cause her to be punished. But for a moment, I’m going to take a quick look at what was called ‘breaking out’, which wasn’t escaping but acting in an irrational way.

Punishment cells

The ‘prison matron’ explained that at Millbank there were 42 matrons of various ranks, and an average of 471 prisoners; that’s about 11 convicts to each warder. She went on:

‘The most trying ordeal for all prisoners is that of probation at Millbank – the silent system, as it may almost be termed… it is simply impossible to make the female prisoners conform to strictly silent rules, or to any rules, for a length of time… there is a restlessness and excitability in the character of these women, that makes the charge of them infinitely more of a labour and a study than the management of treble the number of men.

‘The male prisoners are influenced by some amount of reason and forethought, but the female prisoner… acts more often like a mad woman than a rational, reflecting human being.’ FL

The offending women were put into ‘dark cells’. Mayhew and Binny were shown them as part of their tour of Millbank. ‘”There’s one of our punishment cells,” says the dark-eyed young matron, as we quit B ward, passage No 2. The cell was not quite dark; there was a bed in the corner of it.

‘”What can the women do there?” asked we. “Do!” cried the matron; “why, they can sing and dance, and whistle, and make use, as they do, of the most profane language conceivable.”‘ Dancing and whistling? Disgraceful.

![Women prisoners in the yard at Millbank]()

Women prisoners in the yard at Millbank *

‘We now proceeded up stairs to the punishment cell on the landing. This one was intensely dark, with a kind of grating in the walls for ventilation, but no light-hole; and there was a small raised wooden bed in the corner. The cell was shut in first by a grated gate, then a wooden door, lined with iron, with another door outside that; and then a kind of mattress, or large straw-pad, arranged on a slide before the outer door, to deaden the sound from within. “Those are the best dark cells in all England,” said our guide, as he closed the many doors. ” They’re clean, warm, and well ventilated.” There were five such cells in a line…

‘”That’s one of the women under punishment who’s singing now,” said the matron, as we stood still to listen. “They generally sing. Oh! that’s nothing – that’s very quiet for them. Their language to the minister is sometimes so horrible, that I am obliged to run away with disgust.

‘”Some that we’ve had,” went on the matron, “have torn up their beds. They make up songs themselves all about the officers of the prison. Oh! they’ll have every one in their verses – the directors, the governor, and all of us.” She then repeated the following doggerel from one of the prison songs :- “If you go to Millbank, and you want to see Miss Cosgrove, you must inquire at the round house; – and they’ll add something I can’t tell you of.”

![Engraving of Millbank Prision, 19th century]() ‘We went down stairs and listened to the woman in the dark cell, who was singing “Buffalo Gals,” but we could not make out a word – we could only catch the tune.

‘We went down stairs and listened to the woman in the dark cell, who was singing “Buffalo Gals,” but we could not make out a word – we could only catch the tune.

‘In F ward is the padded cell. “We’ve not had a woman in here for many months,” said the matron, as we entered the place. The apartment was about six feet high; a wainscot of mattresses was ranged all round the walls, and large beds were placed on the ground in one corner, and were big enough to cover the whole cell. “This is for persons subject to fits,” says the matron; “but very few suffer from them.”

‘The matron now led us into a double cell, containing an iron bed and tressel [trestle table]. Here the windows were all broken, and many of the sashes shattered as well. This had been done by one of the women with a tin pot, we were informed.

‘”What is this, Miss Cosgrove ?” asked the warder, pointing to a bundle of sticks like firewood in the corner.

‘”Oh, that’s the remains of her table! And if we hadn’t come in time, she would have broken up her bedstead as well, I dare say…”‘

Isolation

Next they went to ‘D ward, passage No 2; this is the penal ward. Here the windows were wired inside, and had rude kinds of Venetian blinds fixed on the outside; the cells were comparatively dark, and the prisoners younger and much prettier than any we had yet seen. Many of them smiled impudently as we passed. Here the bedding was ranged in square bundles all along the passage, because the prisoners had been found to wear them for bustles.

![Millbank Prison convict in a canvas dress]()

Millbank convict in a canvas dress *

‘”Those bells,” points out the matron, “are to call male officers in case of alarm.”

Presently we saw, inside one of the cells we passed, a girl in a coarse canvas dress, strapped over her claret-brown convict clothes. This dress was fastened by a belt and straps of the same stuff, and, instead of an ordinary buckle, it was held tight by means of a key acting on a screw attached to the back. The girl had been tearing her clothes, and the coarse canvas dress was put on to prevent her repeating the act…

‘The canvas dress we found to be like a coarse sack, with sleeves, and straps at the waist – the latter made to fasten, as we have said before, with small screws. With it we were shown the prison strait-waistcoat, which consisted of a canvas jacket, with black leathern sleeves, like boots closed at the end, and with straps up the arm.

‘The canvas dress has sometimes been cut up by the women with bits of broken glass. Formerly the women used to break the glass window in the penal ward, by taking the bones out of their stays and pushing them through the wires in front.’ M&B

When they knew that the punishment cells were full, ‘women will break their windows, or strike… their officers… knowing that they will have a companion for a day or two; and a companion, even with bread and water by way of diet, is better than silent existence under separate confinement,’ the ‘prison matron’ wrote. Some prisoners ‘feigned’ madness in order to get out of their solitary cells. But Celestina wasn’t one of these.

There’s much more about break-outs and ‘the dark’ in Female Life in Prison, if you’re interested.

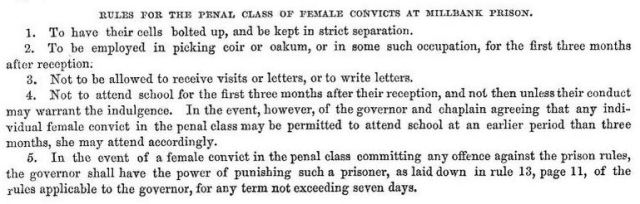

![Rules for the penal class of female convicts at Millbank Prison]()

Rules pinned up at Millbank *

Millbank Prison was ‘founded on humane and rational principles; in which the prisoners should be separated into classes, be compelled to work, and their religious and moral habits properly attended to,’ according to London and its Environs; or, the General Ambulator, a guidebook printed in 1820.

Admirable in theory, perhaps; but in real life being locked up alone and in silence was worse for many of these women than having human contact, even in a punishment cell.

So it’s probably no surprise that being ‘allowed’ to act as servants to matrons was seen as a favour to the better-behaved prisoners. The ‘matron’ listed some of the ways they could get ‘breaks in the monotony of their existence’, such as ‘letter-writing days’ – their letters were opened and read before leaving the prison; ‘schooling’; ‘extra duties out of their cell, in attendance on a matron’; ‘association’, for instance in the prison yard at exercise time; ‘seeing directors, to make remonstrances, or solicit extra favours’; and ‘seeing the surgeon about their little ailments’. FL

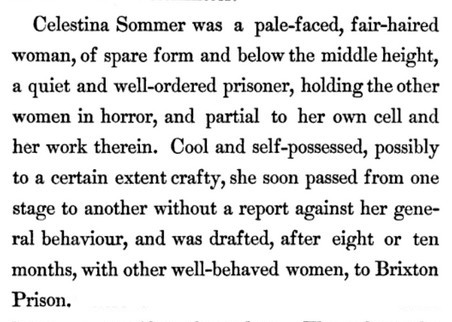

But, as I mentioned, Celestina didn’t break out. The ‘matron’ described her as being ‘quiet and well-ordered… partial to her own cell and her work therein’. This earned her the reward of a transfer to Brixton Prison, which is where I’ll take up her story in the next post.

![Millbank CS crop]()

Further reading:

Memorials of Millbank, Arthur Griffiths, 1884

The Criminal Prisons of London and Scenes of London Life, Henry Mayhew and John Binny, 1862

Female life in prison, by a prison matron, Vol 1, Frederick William Robinson, 1863

London and its Environs; or, the General Ambulator, 1820

* Picture credits:

Prison record: FindMyPast

Plan of Millbank Penitentiary: Wikipedia

Both images of Millbank women convicts in the exercise yard: Memorials of Millbank

Other images inside Millbank Prison, and the two prison notices: The Criminal Prisons of London and Scenes of London Life

Catch up with A Christmas tale:

Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4 | Part 5 | Part 6 | Part 7 | Part 8 | Part 9 | Part 10 | Part 11 | Part 12 | Part 13 | Part 14 | Part 15 | Part 16 | Part 17 | Part 18 | Part 19 | Part 20 | Part 21 | Part 22

![]()

And it was Julia who reported the birth, as the ‘occupier of the house’. So baby Celestina had been born at the Harringtons’ house (perhaps Julia helped with the birth?) and lived with them for the 10 years of her short life. Blood ties apart, she was part of the family.

And it was Julia who reported the birth, as the ‘occupier of the house’. So baby Celestina had been born at the Harringtons’ house (perhaps Julia helped with the birth?) and lived with them for the 10 years of her short life. Blood ties apart, she was part of the family. Poor Julia. Imagine the horror of seeing her little charge lying dead, the victim of murder. I hope the police had thought to cover the throat wound.

Poor Julia. Imagine the horror of seeing her little charge lying dead, the victim of murder. I hope the police had thought to cover the throat wound. But what could Julia have done? It was little Celestina’s mother who took the girl away. She’d said she couldn’t afford to pay the 2/6 a week any more. Julia’d had no right to stop her. Not that that would help with her grief now. And her name was now in the papers, linked with a sensational crime. Even if people who knew her couldn’t read, word would get round. Her troubles had probably only just begun.

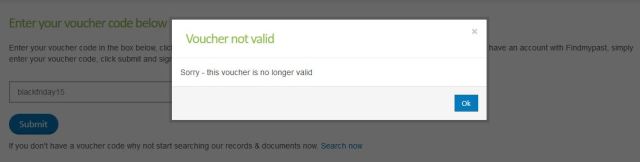

But what could Julia have done? It was little Celestina’s mother who took the girl away. She’d said she couldn’t afford to pay the 2/6 a week any more. Julia’d had no right to stop her. Not that that would help with her grief now. And her name was now in the papers, linked with a sensational crime. Even if people who knew her couldn’t read, word would get round. Her troubles had probably only just begun. Elizabeth and Charles Grobe lived at 16 Murray Street, now called Murray Grove. Next door to them, at no 17, another murder had been committed. Mary McNeil (McNeill, M’Neil in some newspapers) had cut the throats of her two illegitimate sons. Well, OK, you may say, that was a sad and not uncommon crime in Victorian days.

Elizabeth and Charles Grobe lived at 16 Murray Street, now called Murray Grove. Next door to them, at no 17, another murder had been committed. Mary McNeil (McNeill, M’Neil in some newspapers) had cut the throats of her two illegitimate sons. Well, OK, you may say, that was a sad and not uncommon crime in Victorian days. Here we have ‘intense and painful’ excitement outside the police court as a well dressed, attractive woman is charged with killing two of her children (one was in the country at the time).

Here we have ‘intense and painful’ excitement outside the police court as a well dressed, attractive woman is charged with killing two of her children (one was in the country at the time). A respectable, genteel person of 25, mother of illegitimate children, who cut their throats with a razor. Is this beginning to

A respectable, genteel person of 25, mother of illegitimate children, who cut their throats with a razor. Is this beginning to

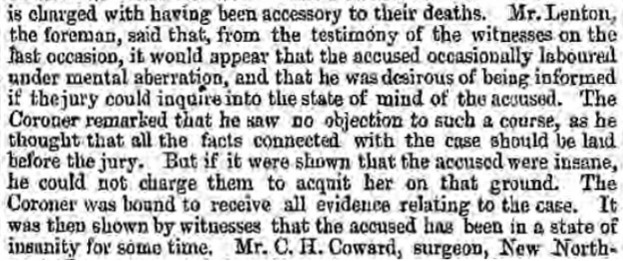

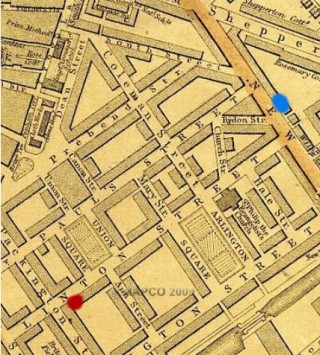

During the court proceedings that followed, her mental health was mentioned several times. Interestingly, the jury at the coroner’s inquest was very concerned about it. Here’s The Era, published on 9 December:

During the court proceedings that followed, her mental health was mentioned several times. Interestingly, the jury at the coroner’s inquest was very concerned about it. Here’s The Era, published on 9 December: It continues:

It continues: I’ve no idea whether the cash box has any echoes in Celestina’s

I’ve no idea whether the cash box has any echoes in Celestina’s

And over on the

And over on the

Here’s another, this time from Micawber St, called Edward St in the 1850s. You can see the houses are a little plainer, perhaps because they’re on a side street. I’ve marked the ones in the photo in yellow on the map:

Here’s another, this time from Micawber St, called Edward St in the 1850s. You can see the houses are a little plainer, perhaps because they’re on a side street. I’ve marked the ones in the photo in yellow on the map: I hope this gives you an idea of the sort of houses Celestina Sommer would’ve known in Murray Grove in 1856. You can compare them to her home in Linton St

I hope this gives you an idea of the sort of houses Celestina Sommer would’ve known in Murray Grove in 1856. You can compare them to her home in Linton St

With such a verdict, the coroner’s only option was to make out a warrant for her to be committed to

With such a verdict, the coroner’s only option was to make out a warrant for her to be committed to

It must have been an intimidating sight for Celestina, for the witnesses, and for officials charged with keeping order – especially after the

It must have been an intimidating sight for Celestina, for the witnesses, and for officials charged with keeping order – especially after the  Just before noon Celestina Sommer was ‘placed in the dock’ before William Corrie, the same magistrate who’d tried her at the

Just before noon Celestina Sommer was ‘placed in the dock’ before William Corrie, the same magistrate who’d tried her at the  Poor Julia, having to go through the details again and knowing her name would once more be splashed in the papers. I wonder if she was afraid of a negative reaction against her giving evidence, after what had happened to the Mount girls after the inquest? But she was only giving the bare facts of Celestina Christmas’s life with her. It couldn’t be seen as snitching to the peelers.

Poor Julia, having to go through the details again and knowing her name would once more be splashed in the papers. I wonder if she was afraid of a negative reaction against her giving evidence, after what had happened to the Mount girls after the inquest? But she was only giving the bare facts of Celestina Christmas’s life with her. It couldn’t be seen as snitching to the peelers. This is odd on many levels. First, talking about performances of Shakespeare plays when she’d just been committed for trial for ‘wilful murder’. Could it have been part of her plan to appear ‘insane’? A way of distracting herself? Or of showing that she was cultured, not a common criminal? Was she genuinely so shocked that she had no idea of what she was talking about? Of course, murder is an important feature of both plays.

This is odd on many levels. First, talking about performances of Shakespeare plays when she’d just been committed for trial for ‘wilful murder’. Could it have been part of her plan to appear ‘insane’? A way of distracting herself? Or of showing that she was cultured, not a common criminal? Was she genuinely so shocked that she had no idea of what she was talking about? Of course, murder is an important feature of both plays.

Which is interesting. Celestina’s husband Charles Sommer said he was the one who paid for the child’s keep; he paid it willingly; and perhaps most interesting, it had been agreed before the marriage that he’d pay. Presumably this was a condition of his getting the wealthy silversmith’s daughter and a decent dowry, but who knows? I don’t think it was a love match, anyway.

Which is interesting. Celestina’s husband Charles Sommer said he was the one who paid for the child’s keep; he paid it willingly; and perhaps most interesting, it had been agreed before the marriage that he’d pay. Presumably this was a condition of his getting the wealthy silversmith’s daughter and a decent dowry, but who knows? I don’t think it was a love match, anyway.

The Era, two days after the trial, had even more to say about what Celestina looked like in the dock:

The Era, two days after the trial, had even more to say about what Celestina looked like in the dock: The journalists in these and other papers were very struck by Celestina’s young appearance and ‘absence of ferocity’. She just didn’t look like a proper murderess should. Victorians judged others on their looks even more than we do now.

The journalists in these and other papers were very struck by Celestina’s young appearance and ‘absence of ferocity’. She just didn’t look like a proper murderess should. Victorians judged others on their looks even more than we do now. These, after all, were the days when people believed that

These, after all, were the days when people believed that

Mr Justice Wightman pointed out that the trial was ‘specially fixed for that morning’. On what ground was the application for postponement made?

Mr Justice Wightman pointed out that the trial was ‘specially fixed for that morning’. On what ground was the application for postponement made? In other words, he needed more time than the week he’d had to find out whether Celestina had been ‘insane’ when she murdered her daughter, Celestina Christmas. If she had been insane, she wouldn’t be sentenced to death. So the consequences were huge.

In other words, he needed more time than the week he’d had to find out whether Celestina had been ‘insane’ when she murdered her daughter, Celestina Christmas. If she had been insane, she wouldn’t be sentenced to death. So the consequences were huge. The Court agreed to postpone Celestina Sommer’s trial until the April session.

The Court agreed to postpone Celestina Sommer’s trial until the April session.

Several papers again commented on how small and young-looking Celestina Sommer was, and that she must’ve been quite young when she

Several papers again commented on how small and young-looking Celestina Sommer was, and that she must’ve been quite young when she

I have to say I find this puzzling. Why would little Celestina have said ‘someone’ was going to cut her throat? Who would have told her that, and why? Or how else would she know? But great stress seems to have been placed on this conversation, and I suppose it was to show that the murder was premeditated.

I have to say I find this puzzling. Why would little Celestina have said ‘someone’ was going to cut her throat? Who would have told her that, and why? Or how else would she know? But great stress seems to have been placed on this conversation, and I suppose it was to show that the murder was premeditated.

It was William Bodkin who asked the second question, as the Proceedings’ report of the cross-examination says:

It was William Bodkin who asked the second question, as the Proceedings’ report of the cross-examination says: So

So  Sergeant Edwin Townsend then took the stand. He repeated the

Sergeant Edwin Townsend then took the stand. He repeated the  Rebecca Anne Donovan was the next witness. She was the ‘female searcher’ at Hoxton Police Station in Robert Street (which no longer exists but may be the current Prestwood St, off Wenlock St, near

Rebecca Anne Donovan was the next witness. She was the ‘female searcher’ at Hoxton Police Station in Robert Street (which no longer exists but may be the current Prestwood St, off Wenlock St, near  It’s odd that the sergeant was saying he’d found the ‘large sharp carving-knife’ on the day Celestina was arrested and the Sommers’ house was searched, 17 February. Yet at the police court hearing Inspector Payne had testified that he’d searched the house on the same day, but ‘could not discover the knife or any weapon with which the wounds were inflicted.’

It’s odd that the sergeant was saying he’d found the ‘large sharp carving-knife’ on the day Celestina was arrested and the Sommers’ house was searched, 17 February. Yet at the police court hearing Inspector Payne had testified that he’d searched the house on the same day, but ‘could not discover the knife or any weapon with which the wounds were inflicted.’ He stated: ‘After I had been there a few minutes, she began talking to herself about Hamlet and Richard the Third – after she had been talking some time, she put her handkerchief to her face, and said, in a low tone, that it was her brother’s child that was dead (that was said to herself), and he was dead, and when he died, she took the child to keep it, and she paid 5s. a week for it, which she paid out of her own earnings, as she taught music, and she did not wish to put the child to service, she was not big enough – she said, “I did it; it is no use telling a lie about it, for I did not know what to do for the best” – she said nothing more about the child – she was talking the whole of the time she was there, about her husband, what he was, and where she lived before they were married – she said her husband was an engraver – I do not remember anything else that she said.’

He stated: ‘After I had been there a few minutes, she began talking to herself about Hamlet and Richard the Third – after she had been talking some time, she put her handkerchief to her face, and said, in a low tone, that it was her brother’s child that was dead (that was said to herself), and he was dead, and when he died, she took the child to keep it, and she paid 5s. a week for it, which she paid out of her own earnings, as she taught music, and she did not wish to put the child to service, she was not big enough – she said, “I did it; it is no use telling a lie about it, for I did not know what to do for the best” – she said nothing more about the child – she was talking the whole of the time she was there, about her husband, what he was, and where she lived before they were married – she said her husband was an engraver – I do not remember anything else that she said.’ His language was cautious, but he, too, mentioned the carving knife and said that he’d seen it at the Coroner’s inquest – again, something which hadn’t been mentioned in newspaper reports.

His language was cautious, but he, too, mentioned the carving knife and said that he’d seen it at the Coroner’s inquest – again, something which hadn’t been mentioned in newspaper reports. I wonder why Celestina’d written Julia a letter. For evidence? When she married Thomas, Julia hadn’t signed the register, just made her mark. Perhaps she could read but not write? She didn’t mention what was in Celestina’s letter.

I wonder why Celestina’d written Julia a letter. For evidence? When she married Thomas, Julia hadn’t signed the register, just made her mark. Perhaps she could read but not write? She didn’t mention what was in Celestina’s letter.

It seems to overstate things for him to say that he didn’t remember a clearer case of murder. But Celestina’s crime had already become in some way special, and it would grow into an iconic cause c

It seems to overstate things for him to say that he didn’t remember a clearer case of murder. But Celestina’s crime had already become in some way special, and it would grow into an iconic cause c We know that

We know that  The Essex Standard added:

The Essex Standard added:

The Hereford Times described her as being in ‘an almost senseless state’.

The Hereford Times described her as being in ‘an almost senseless state’. Others, though, would have been delighted to see her hang, and not on moral grounds. These were the printers and sellers of

Others, though, would have been delighted to see her hang, and not on moral grounds. These were the printers and sellers of

‘A warning take by my sad fate,

‘A warning take by my sad fate, Next is

Next is  ‘Mother dear she kindly said,

‘Mother dear she kindly said, The

The  ‘On the sixteenth of February.

‘On the sixteenth of February.

Elizabeth Fry had been visiting women in Newgate and, later, other prisons since 1813 and had made many improvements to their lives. The engraving shown here, produced in the 1860s but purporting to show her reading to prisoners in 1816, looks at first fairly sentimentalised. But not all the women are listening with regret and humility; some are hiding playing cards or bottles of booze. There’s a great post which discusses this image, and the issues of women prisoners and prison reform,

Elizabeth Fry had been visiting women in Newgate and, later, other prisons since 1813 and had made many improvements to their lives. The engraving shown here, produced in the 1860s but purporting to show her reading to prisoners in 1816, looks at first fairly sentimentalised. But not all the women are listening with regret and humility; some are hiding playing cards or bottles of booze. There’s a great post which discusses this image, and the issues of women prisoners and prison reform,

A cynic might think that it wasn’t very surprising that the woman were ‘anxious… to obtain pardon’. But after decades of prison visiting, Miss Frazer could probably tell when her audience was faking.

A cynic might think that it wasn’t very surprising that the woman were ‘anxious… to obtain pardon’. But after decades of prison visiting, Miss Frazer could probably tell when her audience was faking.

This Mr Humphreys was probably William Corne Humphreys, whose office was near the Old Bailey in Newgate Street. He doesn’t seem to have been mentioned before in the documents regarding her case.

This Mr Humphreys was probably William Corne Humphreys, whose office was near the Old Bailey in Newgate Street. He doesn’t seem to have been mentioned before in the documents regarding her case.

She was under the category of ‘Prisoners whose Judgments have been respited or from Various Causes remain in Custody from time to time Brought into Court for Trial or Otherwise. Usually called Prisoners upon Orders’ (

She was under the category of ‘Prisoners whose Judgments have been respited or from Various Causes remain in Custody from time to time Brought into Court for Trial or Otherwise. Usually called Prisoners upon Orders’ (

Oh, no! Was it because I’m in the UK and Thomas MacEntee’s link was from the US, Judy’s from Australia? But why would that make a difference? Both the links took me to the UK site, after all.

Oh, no! Was it because I’m in the UK and Thomas MacEntee’s link was from the US, Judy’s from Australia? But why would that make a difference? Both the links took me to the UK site, after all. Third time lucky, I thought, and clicked through. Sweet as a nut! The discount code applied automatically and I paid my half price. So I’ve got my year’s sub after all. Thanks, Claire!

Third time lucky, I thought, and clicked through. Sweet as a nut! The discount code applied automatically and I paid my half price. So I’ve got my year’s sub after all. Thanks, Claire!

That’s a much older (and slightly sinister) version of Father Christmas

That’s a much older (and slightly sinister) version of Father Christmas

And taking into consideration

And taking into consideration

‘We went down stairs and listened to the woman in the dark cell, who was singing “

‘We went down stairs and listened to the woman in the dark cell, who was singing “